The Text is given from Jamieson's Popular Ballads, as taken down by him from Mrs. Brown's recitation.

The Story of the ballad is told at length in at least two ancient monastic records; in the Annals of the Monastery of Waverley, the first Cistercian house in England, near Farnham, Surrey (edited by Luard, vol. ii. p. 346, etc., from MS. Cotton Vesp, A. xvi. fol. 150, etc.); more fully in the Annals of the Monastery at Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire (edited by Luard, vol. i. pp. 340, etc., from MS. Cotton Vesp. E. iii. fol. 53, etc.). Both of these give the date as 1255, the latter adding July 31. Matthew Paris also tells the tale as a contemporary event. The details may be condensed as follows.

All the principal Jews in England being collected at the end of July 1255 at Lincoln, Hugh, a schoolboy, while playing with his companions (jocis ac choreis) was by them kidnapped, tortured, and finally crucified. His body was then thrown into a stream, but the water, tantam sui Creatoris injuriam non ferens, threw the corpse back on to the land. The Jews then buried it; but it was found next morning above-ground. Finally it was thrown into a well, which at once was lit up with so brilliant a light and so sweet an odour, that word went forth of a miracle. Christians came to see, discovered the body floating on the surface, and drew it up. Finding the hands and feet to be pierced, the head ringed with bleeding scratches, and the body otherwise wounded, it was at once clear to all tanti sceleris auctores detestandos fuisse Judaeos, eighteen of whom were subsequently hanged.

Other details may be gleaned from various accounts. The name of the Jew into whose house the boy was taken is given as Copin or Jopin. Hugh was eight or nine years old. Matthew Paris adds the circumstance of Hugh's mother (Beatrice by name) seeking and finding him.

The original story has obviously become contaminated with others (such as Chaucer's Prioresses Tale) in the course of six hundred and fifty years. But the central theme, the murder of a child by the Jews, is itself of great antiquity; and similar charges are on record in Europe even in the nineteenth century. Further material for the study of this ballad may be found in Francisque Michel's Hugh de Lincoln (1839), and J. O. Halliwell [-Phillipps]'s Ballads and Poems respecting Hugh of Lincoln (1849).

Percy in the Reliques (1765), vol. i. p. 32, says:-- 'If we consider, on the one hand, the ignorance and superstition of the times when such stories took their rise, the virulent prejudices of the monks who record them, and the eagerness with which they would be catched up by the barbarous populace as a pretence for plunder; on the other hand, the great danger incurred by the perpetrators, and the inadequate motives they could have to excite them to a crime of so much horror, we may reasonably conclude the whole charge to be groundless and malicious.'

The tune 'as sung by the late Mrs. Sheridan' may be found in John Stafford Smith's Musica Antiqua (1812), vol. i. p. 65, and Motherwell's Minstrelsy, tune No. 7.

SIR HUGH, OR THE JEW'S DAUGHTER

1.

Four and twenty bonny boys

Were playing at the ba',

And by it came him sweet Sir Hugh,

And he play'd o'er them a'.

2.

He kick'd the ba' with his right foot,

And catch'd it wi' his knee,

And throuch-and-thro' the Jew's window

He gard the bonny ba' flee.

3.

He's doen him to the Jew's castell,

And walk'd it round about;

And there he saw the Jew's daughter,

At the window looking out.

4.

'Throw down the ba', ye Jew's daughter,

Throw down the ba' to me!'

'Never a bit,' says the Jew's daughter,

'Till up to me come ye.'

5.

'How will I come up? How can I come up?

How can I come to thee?

For as ye did to my auld father,

The same ye'll do to me.'

6.

She's gane till her father's garden,

And pu'd an apple red and green;

'Twas a' to wyle him sweet Sir Hugh,

And to entice him in.

7.

She's led him in through ae dark door,

And sae has she thro' nine;

She's laid him on a dressing-table,

And stickit him like a swine.

8.

And first came out the thick, thick blood,

And syne came out the thin,

And syne came out the bonny heart's blood;

There was nae mair within.

9.

She's row'd him in a cake o' lead,

Bade him lie still and sleep;

She's thrown him in Our Lady's draw-well,

Was fifty fathom deep.

10.

When bells were rung, and mass was sung,

And a' the bairns came hame,

When every lady gat hame her son,

The Lady Maisry gat nane.

11.

She's ta'en her mantle her about,

Her coffer by the hand,

And she's gane out to seek her son,

And wander'd o'er the land.

12.

She's doen her to the Jew's castell,

Where a' were fast asleep:

'Gin ye be there, my sweet Sir Hugh,

I pray you to me speak.'

13.

She's doen her to the Jew's garden,

Thought he had been gathering fruit:

'Gin ye be there, my sweet Sir Hugh,

I pray you to me speak.'

14.

She near'd Our Lady's deep draw-well,

Was fifty fathom deep:

'Whare'er ye be, my sweet Sir Hugh,

I pray you to me speak.'

15.

'Gae hame, gae hame, my mither dear.

Prepare my winding sheet,

And at the back o' merry Lincoln

The morn I will you meet.'

16.

Now Lady Maisry is gane hame,

Made him a winding sheet,

And at the back o' merry Lincoln

The dead corpse did her meet.

17.

And a' the bells o' merry Lincoln

Without men's hands were rung,

And a' the books o' merry Lincoln

Were read without man's tongue,

And ne'er was such a burial

Sin Adam's days begun.

Sir Hugh, Or The Jew's Daughter

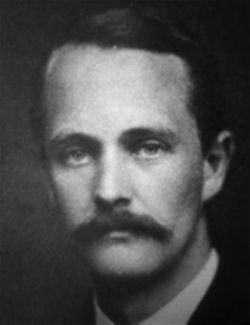

Frank Sidgwick

Suggested Poems

Explore a curated selection of verses that share themes, styles, and emotional resonance with the poem you've just read.